How I Didn’t Stalk Robert Crumb

(But I Did Get Schooled About Steamboats)

IAN DAVID MARSDEN — NOV 30, 2025

By Ian David Marsden

Substack: https://iandavidmarsden.substack.com/p/how-i-didnt-stalk-robert-crumb

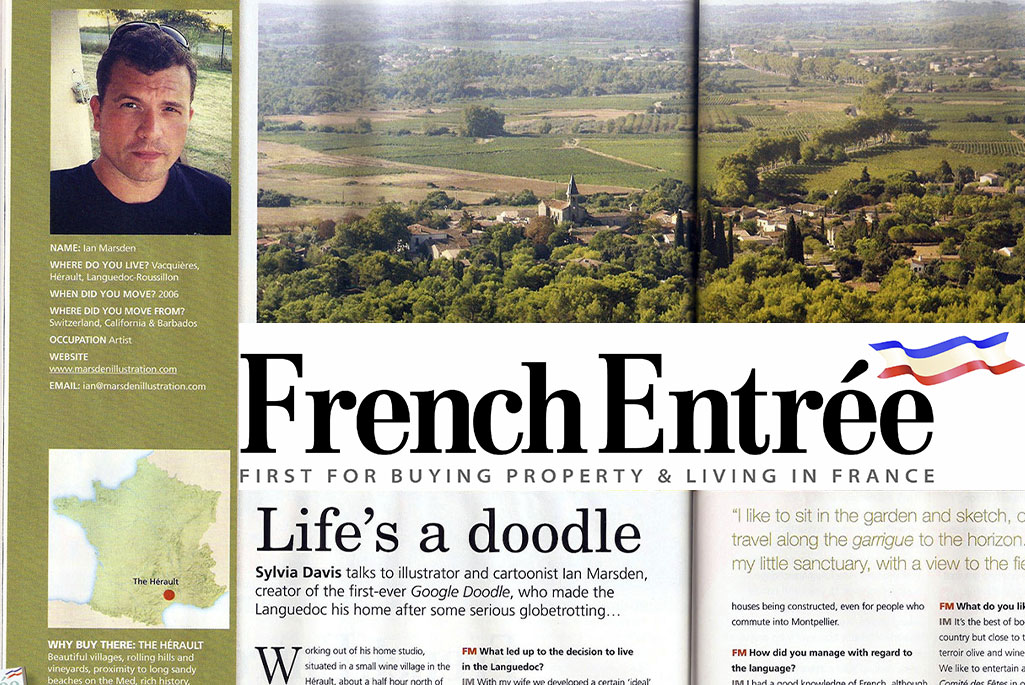

In 2006, I committed an act of transatlantic defection, trading the over-caffeinated bustle of the United States for a tiny, sun-blasted village in the Languedoc region of the South of France—the kind with Roman stones, irregular tavern hours, and eight wineries for every cartoonist. Really good wineries.

Professionally, I was still doing everything you’ll find on my site or by googling me (and I encourage you to do both, just not at the dinner table). But personally, I had chosen escape: from traffic, from the churn, and from that particular flavor of American overstimulation that turns a simple walk to the post office into a tactical ops.

However, the rural French bush telegraph operates at speeds that defy physics. No sooner had I unpacked my nibs and Bristol board than the local populace—farmers, winemakers, and a mix of colorful expatriates—began to circle. Upon learning that the new arrival was an American who drew pictures for a living, a single question began to repeat with the frequency of a skipping record:

“Tiens, vous savez… Crumb habite pas loin.” “Tu connais Crumb, non?”

Robert Crumb? That Crumb? The godfather of underground comix? The man whose pen line jittered with such unnerving precision that even his scribbles looked like they could sue you for plagiarism? It appeared he was not merely a legend, but a neighbor. Just two villages over.

Now, I must clarify my stance on celebrity interaction. Having spent years in Santa Monica, I was well-versed in the protocol of the “cool nod.” You stand behind movie stars at Jamba Juice. You see absolute rock legends parking next to you at Venice Beach. You pretend to be deeply fascinated by the nutritional label on your organic yogurt while a sitcom actor blocks the aisle. As a native New Yorker, I can say it’s almost the same rule you learn in Manhattan about the crazy naked guy shouting at you in the subway: No eye contact. Except it’s Matt Damon having a latte with Steve Martin.

I am, in this regard, a genetic disappointment to my father. My father was a man who viewed celebrity not as a barrier, but as an invitation to immediate intimacy. I carry the emotional scar tissue of a dinner circa 1978, in a hushed, fine-dining establishment, where my father spotted Stevie Wonder passing by on the way to his table. While the rest of the room maintained a respectful murmur, my father sprang from his chair like a jack-in-the-box—cutlery flying—with the unfiltered glee of a man seeing an old army buddy in a pub in Manchester, and bellowed: “HEY STEVIE! I LOVE YOU MAN!!!”

I was twelve. I wanted to dissolve into the carpet. I vividly recall the security detail pivoting toward us, tense as piano wire, calculating whether to neutralize the threat or merely shield the musical genius from aggressive affection. To his eternal credit, Stevie—once he realized he wasn’t being assassinated—laughed it off with grace.

My father was full of such stories. He would often regale us with the tale of the night he was “invited” to hang out with B.B. King and his band in the late sixties in Greenwich Village after a set—an evening of blues and brotherhood that allegedly concluded with my father receiving a tab for vintage Courvoisiers that could have financed a small military coup. But then, the man was in advertising; he was a master of weaving tall tales, a professional blurring of lines, so one was never quite sure where the reality ended and the Madison Avenue copy began. But I digress…

So, despite the proximity of Robert Crumb, I had no intention of recreating the “Stevie Incident” or risking a B.B. King-level bar tab in the Languedoc. I had not crossed the Atlantic to hunt fellow Americans.

And yet… this was Crumb. To a cartoonist, this is a foundational text. I decided that a digital intrusion would be gauche, and a phone call too aggressive. I would opt for the gentleman’s approach. I sat down and penned a short, handwritten note. It was brief, respectful, and cleanly printed—because even for cartoonists, there is a right way to say bonjour. I might even have added a small drawing, as I am apt to do, but I don’t remember. I do remember, that I specifically mentioned that I was living in the area by pure hazard and that I was NOT stalking him.

The Return Volley

I dropped my letter into the yellow post box outside our local mairie, just across from the village café—did I mention that I lived in a village that would not have been out of place as a setting in the movie Chocolat?—and prepared myself for the Sound of Silence. I had done my duty. I had been the polite neighbor. I fully expected my note to be filed in a recycling bin in Sauve, perhaps briefly glanced at by a secretary or going under in the piles of actual, interesting correspondence.

I certainly did not expect a return volley. And I absolutely did not expect it to arrive with the velocity of a court summons.

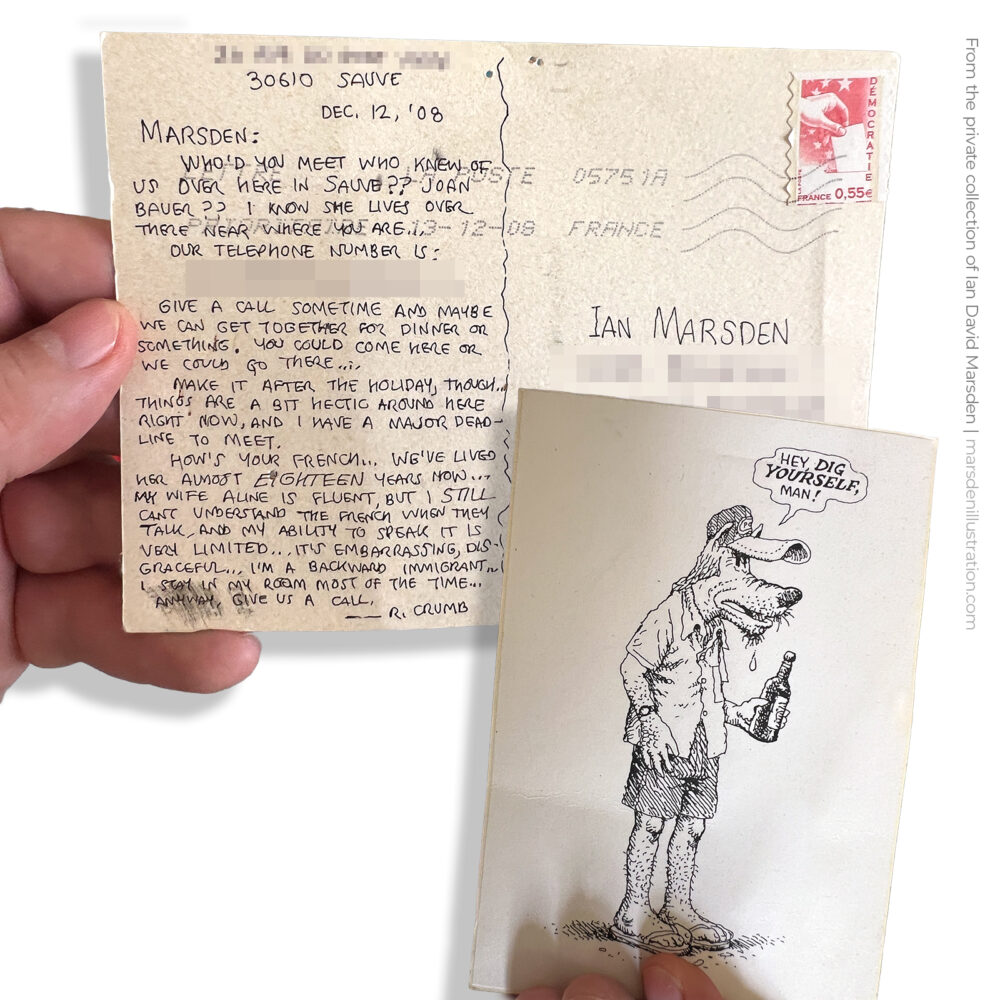

Almost by return post, a card appeared in my mailbox.

To understand the gravity of this moment, you must understand the typography. Most people receive bills, flyers for discount heating oil, or postcards from aunts featuring sunsets. I was holding a piece of stiff cardstock featuring a disheveled, anthropomorphic dog clutching a bottle, barking the phrase: “HEY DIG YOURSELF, MAN!”

I turned it over. The handwriting was unmistakable. It was The Font. The nervous, wobble-free, all-caps lettering that had chronicled the neurotic breakdowns of Fritz the Cat and Mr. Natural was now spelling out my own name.

“MARSDEN:”

It was not a cease-and-desist. It was not a restraining order. It was, bafflingly, a chatty missive from a neighbor looking to connect. He asked who I knew in the area (“JOAN B…?”), suggested we get together (“GIVE A CALL SOMETIME AND MAYBE WE CAN GET TOGETHER FOR DINNER OR SOMETHING”), and then, in a twist that instantly endeared him to me, launched into a paragraph of exquisite, neurotic vulnerability regarding his integration into French society.

Here was the Titan of Underground Comix, a man whose work is collected in museums, confessing to me—a total stranger—that after eighteen years in the country, his French was still a disaster.

“MY WIFE ALINE IS FLUENT, BUT I STILL CAN’T UNDERSTAND THE FRENCH WHEN THEY TALK… IT’S EMBARRASSING, DISGRACEFUL… I’M A BACKWARD IMMIGRANT… I STAY IN MY ROOM MOST OF THE TIME.”

It was disarming. It was hilarious. It was tragically relatable. The “Stevie Wonder Incident” paranoia evaporated. This wasn’t a celebrity; this was a guy who just happened to draw better than anyone else on earth, admitting that the subjunctive tense scared him as much as it scared me.

I picked up the phone.

Dinner at the Museum

I dialed the number. The earth did not open up, nor did a choir of underground comix angels sing. A human being answered. The man himself. Friendly, open, inviting. And just like that, the barrier was breached.

That first phone call segued into a dinner invitation, which led me to the Crumb residence in Sauve. Stepping into their home was less like visiting a neighbor and more like walking into a living, breathing panel of one of his comics. It was a marvelous, multi-level French townhouse overlooking the river, a curated habitat where every room felt like a miniature museum of the eclectic. It was precisely as cluttered-yet-organized, warm, and visually dense as you would hope Robert Crumb’s house to be—a sanctuary of vinyl, paper, little objects, shining lights, decorations, and vintage ephemera.

I met Aline, Robert’s wife and fellow cartoonist, who was the vivacious, fluent-French-speaking, yoga-class-giving counterweight to Robert’s “backward immigrant” persona. We spent a wonderful evening dissecting the absurdities of life, art, and the peculiar mechanics of living in the south of France.

From that point on, our paths crossed sporadically—sometimes by design, mostly by the happy accidents of village life. The epicenter of these collisions was usually the Vidourle Prix, a gallery situated just across the first bridge leading into town. Co-managed by Aline, the gallery is to this day a vortex of creative eccentricity. It wasn’t just a showcase for Robert and Aline, or their daughter Sophie (also a cartoonist); it had become a crystallization point for a dozen or so highly eccentric artists—Americans and international castaways—who had somehow washed up on the shores of the Vidourle river or congregated at specific solstices indicated by the dolmen up in the Mer de Rochers in Sauve, perhaps.

It was there, amidst the art and the books, that one can on rare occasions find Robert playing piano or banjo, surrounded by musical ensembles so ragtag and visually specific that they appeared to be drawn directly from his sketchbook. Under normal circumstances, I might have questioned whether these musicians were real or merely the result of a contact high. However, unlike Crumb, my experience with LSD and other hallucinogenics is entirely non-existent. Therefore, I was forced to conclude that they must be real. And delightfully so.

The PEGOT and the Pandemic

Fast forward a few years. Through the tireless machinations of my wonderful literary agent, Anna Olswanger—a woman whose tenacity is matched only by her slightly alarming belief in my potential—I finally landed the white whale of the cartooning profession: a publishing contract for my first solo graphic novel.

The subject was no small fry. It was Marvin: Based on The Way I Was, a graphic biography of Marvin Hamlisch. For the uninitiated, Hamlisch was one of only two people in history to achieve the PEGOT—the Royal Flush of entertainment awards: Pulitzer, Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony. My job was to adapt his life story, chronicling the family’s escape from Nazi-occupied Austria, his acceptance into Juilliard at the preposterous age of six, and the crippling performance anxiety that plagued him even as he was racking up hits with Liza Minnelli and Barbra Streisand.

It was a labor of love, ink, and caffeine. The result was a handsome 64-page volume published by Schiffer, a tangible proof of my existence as an author. The publication date was set. The presses rolled. Champagne was chilled.

And then, the universe decided to execute a punchline that was less “Woody Allen” and more The Book of Revelation.

The year was 2020.

My book, a story about a man overcoming paralyzing anxiety, was released into a world that was collectively having a panic attack. As the delivery trucks left the warehouse, the shutters came down on civilization. Bookstores locked their doors. Libraries went dark. Literary festivals were cancelled with extreme prejudice.

Marvin was launched not with a bang, but into a vacuum. The critics, to their credit, were lovely. The reviews were glowing. But trying to sell a biography in physical bookstores during a global lockdown was like trying to sell hearing aids at a mime convention. Libraries that would have hosted reading events were shuttered. As is always the case, you can’t hype something that came out six months earlier. So Marvin, sadly, remains known only to the initiated few.

The Critique from the Master

With the world in lockdown and my book launch echoing into the void, I realized I had one potential reader who was (A) accessible by local post, and (B) arguably the inventor of the modern autobiographical graphic novel.

(But I Did Get Schooled About Steamboats)

IAN DAVID MARSDEN — NOV 30, 2025

By Ian David Marsden

In 2006, I committed an act of transatlantic defection, trading the over-caffeinated bustle of the United States for a tiny, sun-blasted village in the Languedoc region of the South of France—the kind with Roman stones, irregular tavern hours, and eight wineries for every cartoonist. Really good wineries.

Professionally, I was still doing everything you’ll find on my site or by googling me (and I encourage you to do both, just not at the dinner table). But personally, I had chosen escape: from traffic, from the churn, and from that particular flavor of American overstimulation that turns a simple walk to the post office into a tactical ops.

However, the rural French bush telegraph operates at speeds that defy physics. No sooner had I unpacked my nibs and Bristol board than the local populace—farmers, winemakers, and a mix of colorful expatriates—began to circle. Upon learning that the new arrival was an American who drew pictures for a living, a single question began to repeat with the frequency of a skipping record:

“Tiens, vous savez… Crumb habite pas loin.” “Tu connais Crumb, non?”

Robert Crumb? That Crumb? The godfather of underground comix? The man whose pen line jittered with such unnerving precision that even his scribbles looked like they could sue you for plagiarism? It appeared he was not merely a legend, but a neighbor. Just two villages over.

Now, I must clarify my stance on celebrity interaction. Having spent years in Santa Monica, I was well-versed in the protocol of the “cool nod.” You stand behind movie stars at Jamba Juice. You see absolute rock legends parking next to you at Venice Beach. You pretend to be deeply fascinated by the nutritional label on your organic yogurt while a sitcom actor blocks the aisle. As a native New Yorker, I can say it’s almost the same rule you learn in Manhattan about the crazy naked guy shouting at you in the subway: No eye contact. Except it’s Matt Damon having a latte with Steve Martin.

I am, in this regard, a genetic disappointment to my father. My father was a man who viewed celebrity not as a barrier, but as an invitation to immediate intimacy. I carry the emotional scar tissue of a dinner circa 1978, in a hushed, fine-dining establishment, where my father spotted Stevie Wonder passing by on the way to his table. While the rest of the room maintained a respectful murmur, my father sprang from his chair like a jack-in-the-box—cutlery flying—with the unfiltered glee of a man seeing an old army buddy in a pub in Manchester, and bellowed: “HEY STEVIE! I LOVE YOU MAN!!!”

I was twelve. I wanted to dissolve into the carpet. I vividly recall the security detail pivoting toward us, tense as piano wire, calculating whether to neutralize the threat or merely shield the musical genius from aggressive affection. To his eternal credit, Stevie—once he realized he wasn’t being assassinated—laughed it off with grace.

My father was full of such stories. He would often regale us with the tale of the night he was “invited” to hang out with B.B. King and his band in the late sixties in Greenwich Village after a set—an evening of blues and brotherhood that allegedly concluded with my father receiving a tab for vintage Courvoisiers that could have financed a small military coup. But then, the man was in advertising; he was a master of weaving tall tales, a professional blurring of lines, so one was never quite sure where the reality ended and the Madison Avenue copy began. But I digress…

So, despite the proximity of Robert Crumb, I had no intention of recreating the “Stevie Incident” or risking a B.B. King-level bar tab in the Languedoc. I had not crossed the Atlantic to hunt fellow Americans.

And yet… this was Crumb. To a cartoonist, this is a foundational text. I decided that a digital intrusion would be gauche, and a phone call too aggressive. I would opt for the gentleman’s approach. I sat down and penned a short, handwritten note. It was brief, respectful, and cleanly printed—because even for cartoonists, there is a right way to say bonjour. I might even have added a small drawing, as I am apt to do, but I don’t remember. I do remember, that I specifically mentioned that I was living in the area by pure hazard and that I was NOT stalking him.

The Return Volley

I dropped my letter into the yellow post box outside our local mairie, just across from the village café—did I mention that I lived in a village that would not have been out of place as a setting in the movie Chocolat?—and prepared myself for the Sound of Silence. I had done my duty. I had been the polite neighbor. I fully expected my note to be filed in a recycling bin in Sauve, perhaps briefly glanced at by a secretary or going under in the piles of actual, interesting correspondence.

I certainly did not expect a return volley. And I absolutely did not expect it to arrive with the velocity of a court summons.

Almost by return post, a card appeared in my mailbox.

To understand the gravity of this moment, you must understand the typography. Most people receive bills, flyers for discount heating oil, or postcards from aunts featuring sunsets. I was holding a piece of stiff cardstock featuring a disheveled, anthropomorphic dog clutching a bottle, barking the phrase: “HEY DIG YOURSELF, MAN!”

I turned it over. The handwriting was unmistakable. It was The Font. The nervous, wobble-free, all-caps lettering that had chronicled the neurotic breakdowns of Fritz the Cat and Mr. Natural was now spelling out my own name.

“MARSDEN:”

It was not a cease-and-desist. It was not a restraining order. It was, bafflingly, a chatty missive from a neighbor looking to connect. He asked who I knew in the area (“JOAN B…?”), suggested we get together (“GIVE A CALL SOMETIME AND MAYBE WE CAN GET TOGETHER FOR DINNER OR SOMETHING”), and then, in a twist that instantly endeared him to me, launched into a paragraph of exquisite, neurotic vulnerability regarding his integration into French society.

Here was the Titan of Underground Comix, a man whose work is collected in museums, confessing to me—a total stranger—that after eighteen years in the country, his French was still a disaster.

“MY WIFE ALINE IS FLUENT, BUT I STILL CAN’T UNDERSTAND THE FRENCH WHEN THEY TALK… IT’S EMBARRASSING, DISGRACEFUL… I’M A BACKWARD IMMIGRANT… I STAY IN MY ROOM MOST OF THE TIME.”

It was disarming. It was hilarious. It was tragically relatable. The “Stevie Wonder Incident” paranoia evaporated. This wasn’t a celebrity; this was a guy who just happened to draw better than anyone else on earth, admitting that the subjunctive tense scared him as much as it scared me.

I picked up the phone.

Dinner at the Museum

I dialed the number. The earth did not open up, nor did a choir of underground comix angels sing. A human being answered. The man himself. Friendly, open, inviting. And just like that, the barrier was breached.

That first phone call segued into a dinner invitation, which led me to the Crumb residence in Sauve. Stepping into their home was less like visiting a neighbor and more like walking into a living, breathing panel of one of his comics. It was a marvelous, multi-level French townhouse overlooking the river, a curated habitat where every room felt like a miniature museum of the eclectic. It was precisely as cluttered-yet-organized, warm, and visually dense as you would hope Robert Crumb’s house to be—a sanctuary of vinyl, paper, little objects, shining lights, decorations, and vintage ephemera.

I met Aline, Robert’s wife and fellow cartoonist, who was the vivacious, fluent-French-speaking, yoga-class-giving counterweight to Robert’s “backward immigrant” persona. We spent a wonderful evening dissecting the absurdities of life, art, and the peculiar mechanics of living in the south of France.

From that point on, our paths crossed sporadically—sometimes by design, mostly by the happy accidents of village life. The epicenter of these collisions was usually the Vidourle Prix, a gallery situated just across the first bridge leading into town. Co-managed by Aline, the gallery is to this day a vortex of creative eccentricity. It wasn’t just a showcase for Robert and Aline, or their daughter Sophie (also a cartoonist); it had become a crystallization point for a dozen or so highly eccentric artists—Americans and international castaways—who had somehow washed up on the shores of the Vidourle river or congregated at specific solstices indicated by the dolmen up in the Mer de Rochers in Sauve, perhaps.

It was there, amidst the art and the books, that one can on rare occasions find Robert playing piano or banjo, surrounded by musical ensembles so ragtag and visually specific that they appeared to be drawn directly from his sketchbook. Under normal circumstances, I might have questioned whether these musicians were real or merely the result of a contact high. However, unlike Crumb, my experience with LSD and other hallucinogenics is entirely non-existent. Therefore, I was forced to conclude that they must be real. And delightfully so.

The PEGOT and the Pandemic

Fast forward a few years. Through the tireless machinations of my wonderful literary agent, Anna Olswanger—a woman whose tenacity is matched only by her slightly alarming belief in my potential—I finally landed the white whale of the cartooning profession: a publishing contract for my first solo graphic novel.

The subject was no small fry. It was Marvin: Based on The Way I Was, a graphic biography of Marvin Hamlisch. For the uninitiated, Hamlisch was one of only two people in history to achieve the PEGOT—the Royal Flush of entertainment awards: Pulitzer, Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony. My job was to adapt his life story, chronicling the family’s escape from Nazi-occupied Austria, his acceptance into Juilliard at the preposterous age of six, and the crippling performance anxiety that plagued him even as he was racking up hits with Liza Minnelli and Barbra Streisand.

It was a labor of love, ink, and caffeine. The result was a handsome 64-page volume published by Schiffer, a tangible proof of my existence as an author. The publication date was set. The presses rolled. Champagne was chilled.

And then, the universe decided to execute a punchline that was less “Woody Allen” and more The Book of Revelation.

The year was 2020.

My book, a story about a man overcoming paralyzing anxiety, was released into a world that was collectively having a panic attack. As the delivery trucks left the warehouse, the shutters came down on civilization. Bookstores locked their doors. Libraries went dark. Literary festivals were cancelled with extreme prejudice.

Marvin was launched not with a bang, but into a vacuum. The critics, to their credit, were lovely. The reviews were glowing. But trying to sell a biography in physical bookstores during a global lockdown was like trying to sell hearing aids at a mime convention. Libraries that would have hosted reading events were shuttered. As is always the case, you can’t hype something that came out six months earlier. So Marvin, sadly, remains known only to the initiated few.

The Critique from the Master

With the world in lockdown and my book launch echoing into the void, I realized I had one potential reader who was (A) accessible by local post, and (B) arguably the inventor of the modern autobiographical graphic novel.

Sending a comic book to Robert Crumb is a bit like sending a mixtape to Mozart. It is an act of hubris bordered by insanity.

Sending a comic book to Robert Crumb is a bit like sending a mixtape to Mozart. It is an act of hubris bordered by insanity. You are handing your work to the man who defined the medium, inviting him to inspect your crosshatching with eyes that have seen everything.

I put a copy in an envelope, scribbled a note, and sent it off to Sauve. I expected silence. Maybe a polite nod three months later.

Yet again, the Crumb-Speed defied the sluggish laws of the French postal service. And I knew for a fact that this was an insanely busy man.

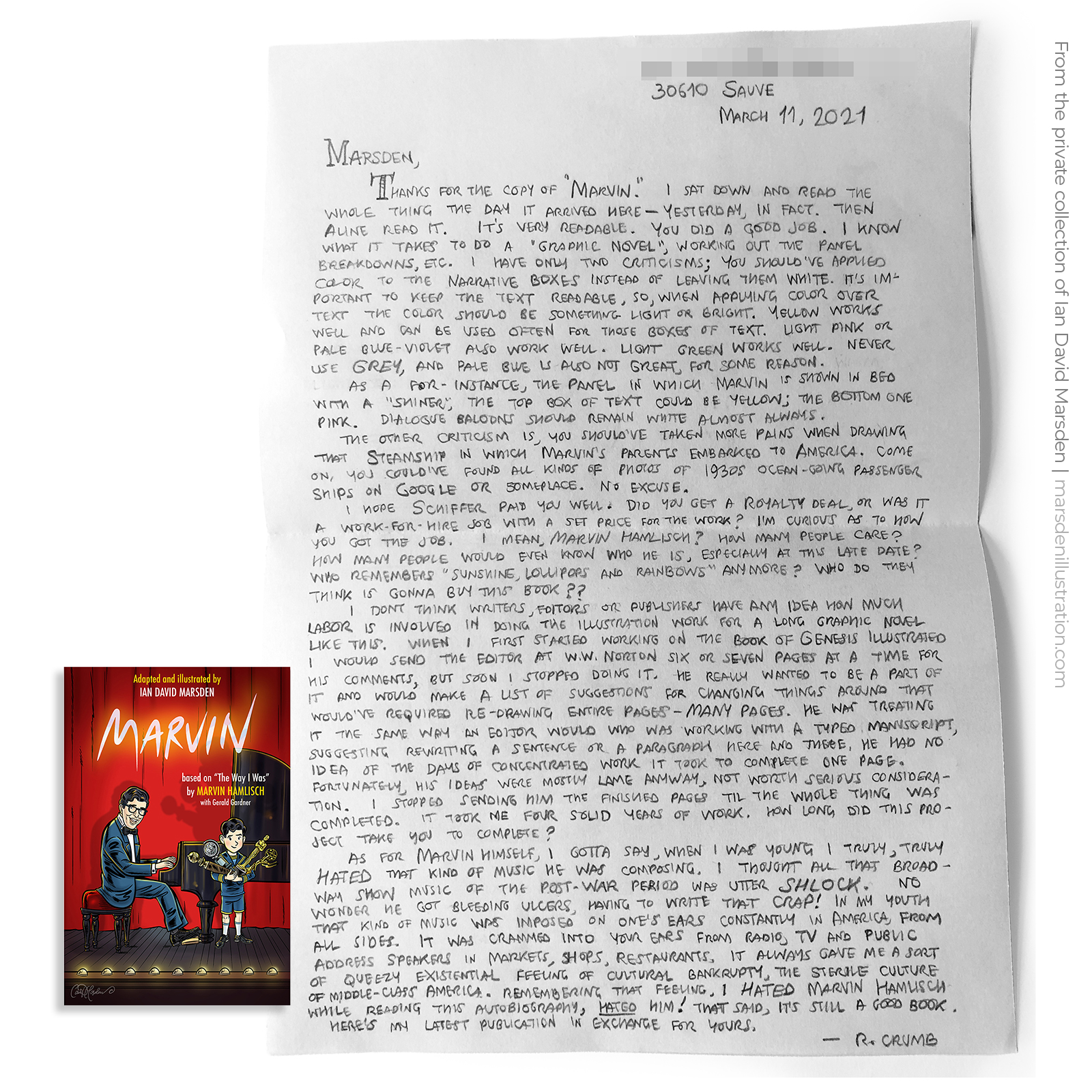

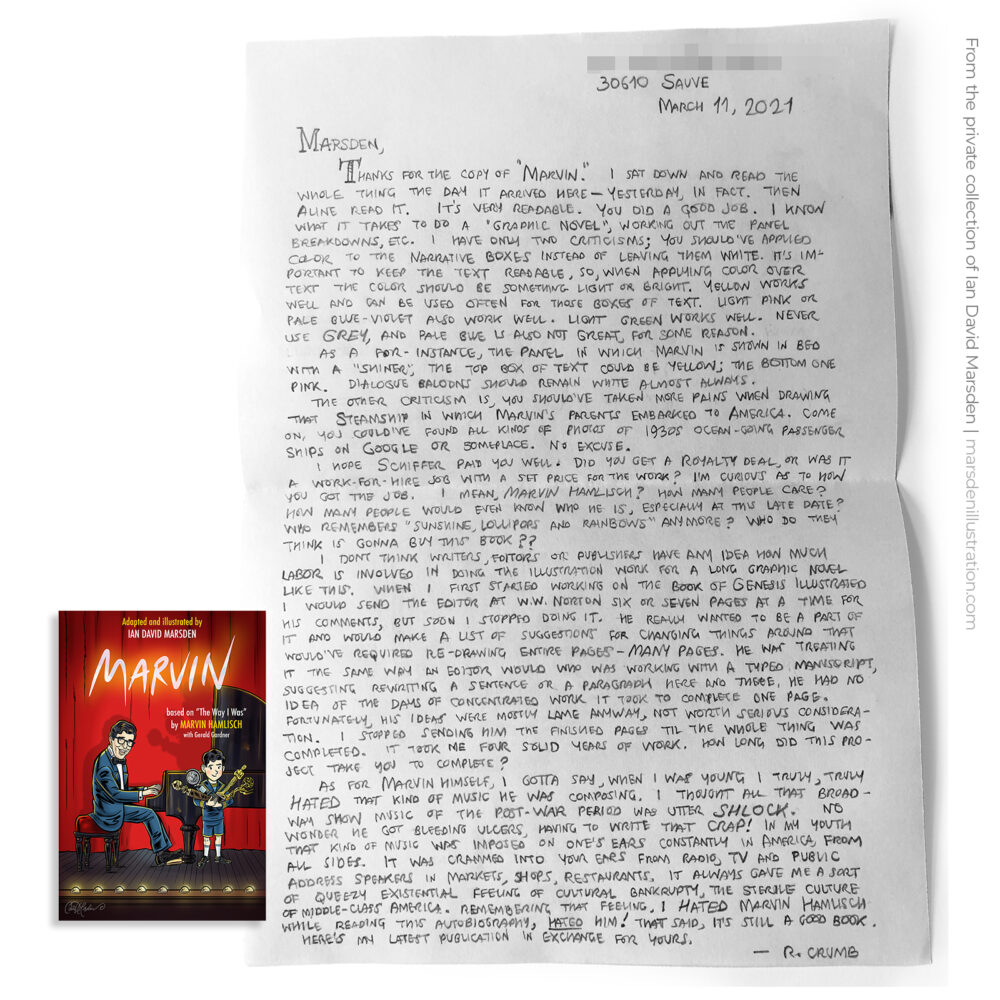

Two, perhaps three days later, a heavy parcel thudded into my mailbox. Inside was a treasure: a beautiful hardcover edition of Robert Crumb Sketchbook Vol. 5, featuring a lovely personal dedication on the flyleaf. But tucked inside was something even more valuable, and infinitely more terrifying: a full-page, handwritten letter.

It was a critique. A detailed, technical, philosophical, and deeply hilarious analysis of my work.

Most people say, “Nice book!” and move on. Crumb sat down, read every panel, analyzed my color choices, critiqued my research methods, and then launched into a tirade against the very subject matter of the biography itself.

It is a document so rich in character that it would be a crime to paraphrase it. I share it here as a testament to the man’s generosity, his exacting standards, and his undying hatred of “shlock.”

MARSDEN,

Thanks for the copy of “MARVIN.” I sat down and read the whole thing the day it arrived here — yesterday, in fact. Then Aline read it. It’s very readable. You did a good job. I know what it takes to do a “Graphic Novel”, working out the panel breakdowns, etc.

I have only two criticisms; You should’ve applied color to the narrative boxes instead of leaving them white. It’s important to keep the text readable, so, when applying color over text the color should be something light or bright. Yellow works well and can be used often for those boxes of text. Light pink or pale blue-violet also work well. Light green works well. NEVER USE GREY, and pale blue is also not great, for some reason.

As a for-instance, the panel in which Marvin is shown in bed with a “shiner”, the top box of text could be yellow; the bottom one pink. Dialogue baloons should remain white almost always.

The other criticism is, you should’ve taken more pains when drawing that STEAMSHIP in which Marvin’s parents embarked to America. Come on, you could’ve found all kinds of photos of 1930s ocean-going passenger ships on Google or someplace. No excuse.

I hope Schiffer paid you well. Did you get a royalty deal, or was it a work-for-hire job with a set price for the work? I’m curious as to how you got the job. I mean, MARVIN HAMLISCH? How many people care? How many people would even know who he is, especially at this late date? Who remembers “Sunshine, Lollipops and Rainbows” anymore? Who do they think is gonna buy this book??

I don’t think writers, editors or publishers have any idea how much LABOR is involved in doing the illustration work for a long graphic novel like this… I stopped sending [my editor] the finished pages til the whole thing was completed. It took me four solid years of work. How long did this project take you to complete?

As for MARVIN himself, I gotta say, when I was young I truly, truly hated that kind of music he was composing. I thought all that Broadway show music of the post-war period was utter SHLOCK. No wonder he got bleeding ulcers, having to write that CRAP! In my youth that kind of music was imposed on one’s ears constantly in America from all sides. It was crammed into your ears from radio, TV and public address speakers in markets, shops, restaurants. It always gave me a sort of queezy existential feeling of cultural bankruptcy, the sterile culture of middle-class America. Remembering that feeling, I HATED MARVIN HAMLISCH while reading this autobiography, HATED HIM! THAT SAID, IT’S STILL A GOOD BOOK.

Here’s my latest publication in exchange for yours.

— R. CRUMB

I put the letter down. I had just been scolded for my steamship research (“No excuse”), given a lesson on color theory (“NEVER USE GREY”), and told that my protagonist represented the “queezy existential feeling of cultural bankruptcy.”

And yet, he finished with: “THAT SAID, IT’S STILL A GOOD BOOK.”

Coming from a man who seemingly hated the music, the era, and the very concept of Marvin Hamlisch with every fiber of his being, this was the highest compliment I could possibly imagine. It was the ultimate validation: The storytelling worked despite the shlock.

I looked at my steamship drawing again. He was right. It was a lazy boat.

About the author:

MARVIN: Based on The Way I Was

Adapted and illustrated by Ian David Marsden

The graphic novel is available in physical bookstores and online.

Order on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Marvin-Based-Way-Was-Hamlisch/dp/0764359045

Publisher: Schiffer Publishing Ltd

ISBN: 9780764359040

If you have purchased a copy, drop me a line—or send me a photo of yourself reading it (preferably not on a lazy steamship), and I might share it.